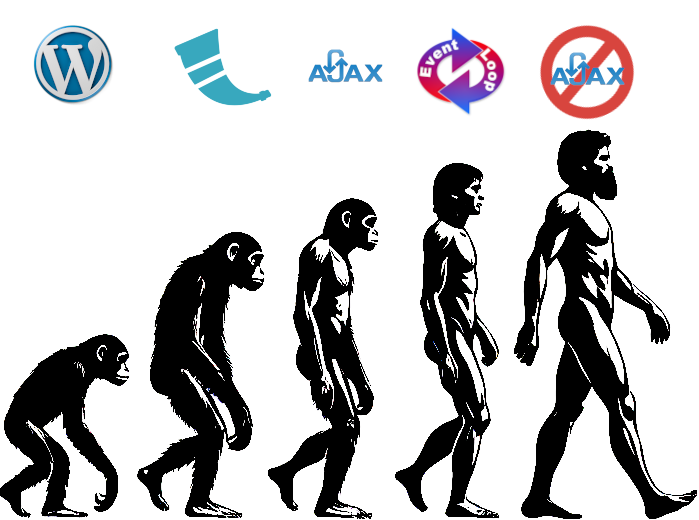

It all started 8 years ago during EuroPython 2017 when Will introduced me to QUADS 1.0 and how their whole client-facing inventory and UI was relying on a heavy WordPress dependency. I was adamant that if I ever joined the team I would replace WordPress with a proper Python web service.

Migration

So we started the migration process thinking that making a Jinja template for each page on our wordpress instance and making a couple of calls to the fresh QUADS 2.0 REST API would suffice but that meant a huge oversight on performance since the pages on WordPress were pre-rendered and only served by the php server. Now we have all our templates and the calls ready so we test in stage which only has 15 servers, unlike our production instance which has ~1300. All good on stage so we merge to production and we ship it. That’s when the fun began.

Ajax Requests

Now we have our new stack in the production instance and we navigate to the inventory and we are presented to a blank page that stays loading for more than 2 minutes. Unacceptable.

We are loading all the data on the flask endpoint, making a bunch of calls at one point and waiting to gather all the data so we can pass it to the Jinja template rendering. In a desperate attempt to make it better we double the Gunicorn workers to find no considerable performance improvements.

Ajax requests come to the rescue.

We realize gathering all that data before the rendering and holding the user from seeing anything loading on the page is going to scare the users away and leave them thinking the server is broken. We move all the data collection logic to ajax requests on each page expecting things would load faster but it’s only the page skeleton which loads while the gathering of the data still takes the same amount of time as before.

Lazy loading

All nice and fancy with the Ajax requests but the performance is still miserable. In comes lazy loading.

Since we had split all the ajax requests for each section and we have one section for each cloud which can be up to 100 concurrent cloud environments, we’d still have to wait for all the requests to be loaded before we can navigate anywhere else. The only sensible change to make would be to only make those requests when the user has the section displayed on their browser view port. With some javascript magic we add an observer that calls the ajax requests only when the component is scrolled to.

const observerOptions = {

root: null, // Use the viewport as the root

rootMargin: '0px',

threshold: 0.1 // Trigger when 10% of the element is visible

};

const observer = new IntersectionObserver((entries, observer) => {

entries.forEach(entry => {

if (entry.isIntersecting) {

const cloudName = entry.target.getAttribute('data-cloud-id');

updateHostsForCloud(cloudName);

observer.unobserve(entry.target);

}

});

}, observerOptions);

$('.cloud-table').each(function() {

observer.observe(this);

});

This reduced the number of requests significantly to only 3 requests initially, 1 for the summary and 2 others for the first 2 clouds which are rendered at the top of the page. We see a considerable improvement with this but we know there is still room for improvement.

Flask Async

Regardless of the great improvements we achieved so far we notice that if there is more than 1 user trying to load the page the responses don’t come through till the other user gets their responses. In comes Flask Async methods.

We can now make all our endpoints async and all our ajax requests as well. This paired with a couple more workers on Gunicorn and we get a much more responsive web.

The Unwanted Requests

Now that we have Async Ajax requests, Async Flask endpoints and lazy loading requests we feel a lot more enterprise ready so we go and stress test our new QUADS web companion till we find there is one more place for improvements. The unwanted requests.

Imagine that you go to the page and the few initial requests are called but you then, out of boredom or curiosity, scroll all the way down triggering the call to all requests and before you get those responses decide to move along to another page. The browser will then say: “nah nah nah, now you sit and wait for all these requests you triggered”. With some additional javascript magic we say abort all ongoing requests if I am navigating away from this page. For that we make a global variable for each request and add a listener for `beforeunload` which gathers all those requests and calls the `abort()` method on.

$(window).on('beforeunload', function() {

// Abort all cloud-specific requests

for (const cloudName in cloudRequests) {

if (cloudRequests[cloudName]) {

cloudRequests[cloudName].abort();

}

}

if (summaryRequest) {

summaryRequest.abort();

}

if (dailyUtilizationRequest) {

dailyUtilizationRequest.abort();

}

if (unmanagedRequest) {

unmanagedRequest.abort();

}

if (faultyRequest) {

faultyRequest.abort();

}

});

Takeaways

The journey from WordPress to a Python-based web service revealed critical insights about scaling web applications for production environments. Here are the essential lessons learned:

- Performance optimization is a step-by-step process, not a one-time fix

This migration story demonstrates that web performance optimization requires an iterative approach with multiple techniques working together to achieve substantial improvements. Each implementation—from Ajax requests to request abortion—addressed specific performance bottlenecks that weren’t apparent until the previous issue was solved.

- User perception matters more than backend speed alone

The initial approach focused solely on backend optimization, but the breakthrough came when prioritizing user experience through progressive loading techniques. Even when data retrieval remained slow, showing users the page skeleton immediately created a more responsive feeling application that kept users engaged rather than frustrated by blank screens.

- Scale testing in production-like environments is essential

The dramatic difference between stage (15 servers) and production (~1300 servers) environments highlights the danger of assuming performance will scale linearly. What works perfectly in a small environment can completely fail when faced with real-world conditions and loads.

Modern web development requires multiple optimization techniques working together

The final solution incorporated several complementary approaches:

- Ajax requests for progressive loading

- Lazy loading to prioritize visible content

- Asynchronous Flask endpoints for concurrent processing

- Request abortion to prevent wasted resources

No single technique solved the performance issues entirely, showing that comprehensive optimization requires a layered strategy rather than seeking a silver bullet.